Episode Photos

Fishermen and divers reporting large aggregations of fish off the coast of Florida discovered there was something attracting the fish to these specific areas - blue holes!

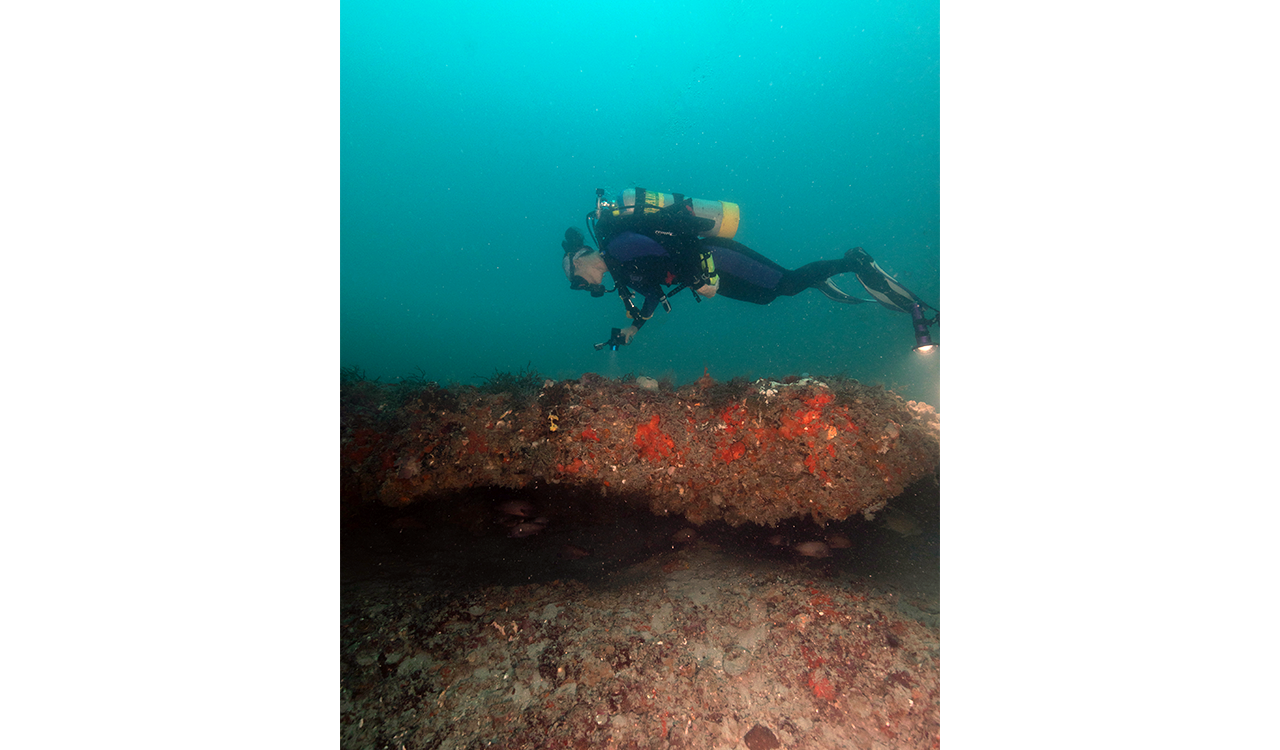

Blue holes are submerged sinkholes and springs that are found on the ocean floor and open up to depths beyond 400 feet. This is the rim of Amberjack Hole off Sarasota, Florida.

Amberjack Hole is named for the schools of amberjack that are commonly found around the hole. Scientists are curious about why marine life like jacks are attracted to these holes.

Scientist Jim Culter of Mote Marine Laboratory is a technical diver that has been collecting data and samples from the blue holes in the Gulf of Mexico.

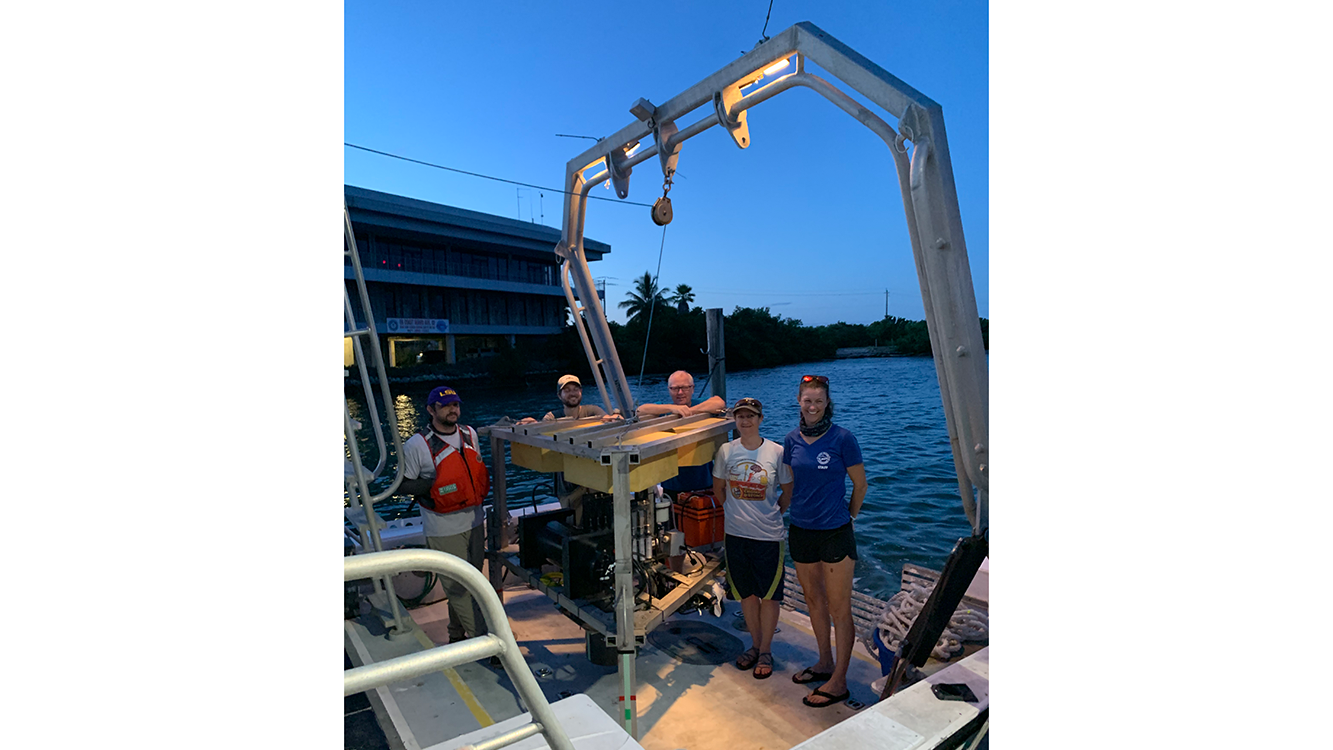

In 2019, Mote Marine Laboratory teamed up with experts from FAU Harbor Branch, Georgia Tech, and the USGS to learn more about these holes.

Scientists aboard the R/V Eugenie Clark - named after the renowned shark and fish biologist and founding director of Mote Marine Laboratory, Dr. Eugenie Clark.

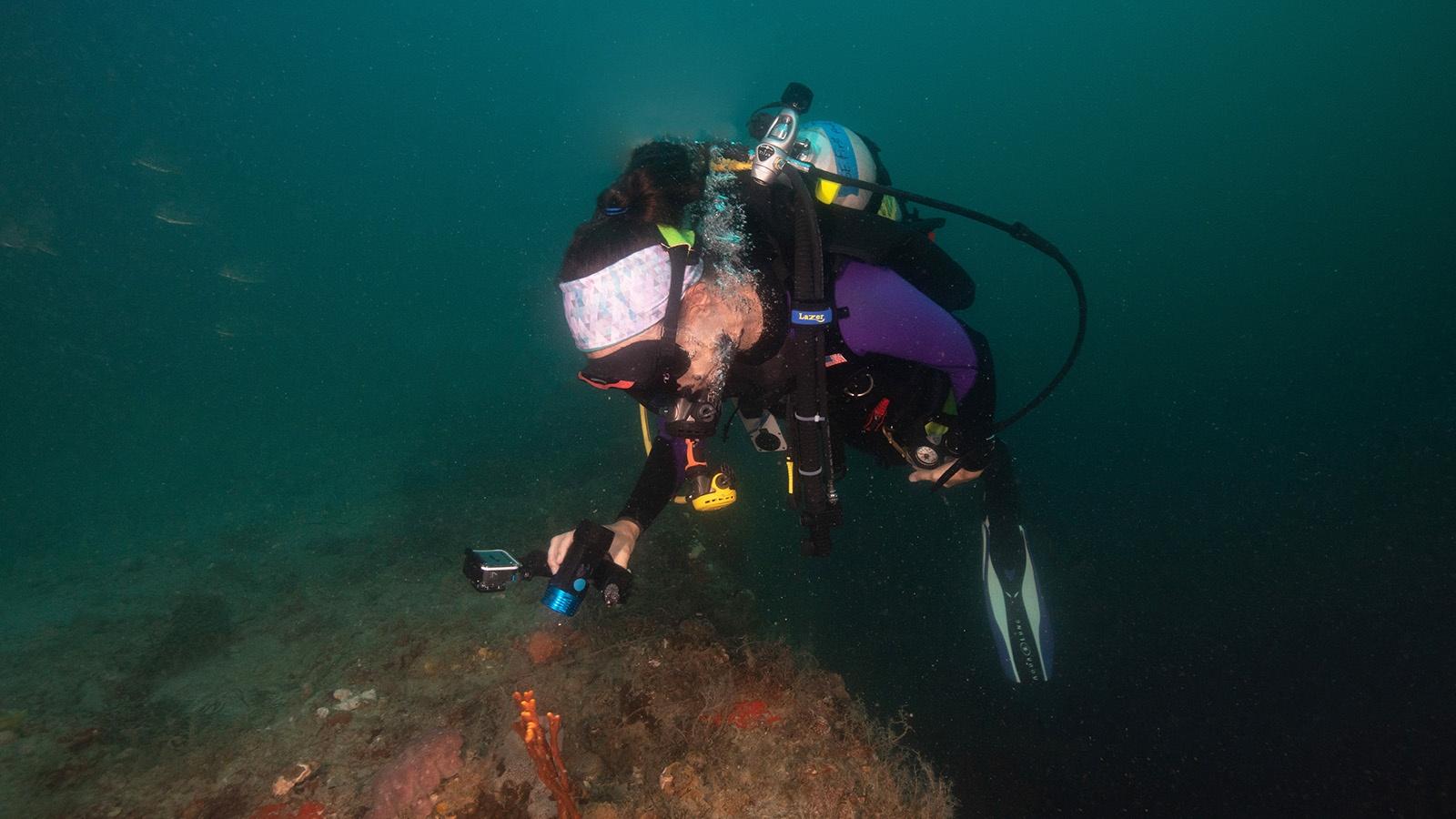

Emily Hall, Ph.D. uses underwater cameras to film marine life around the hole.

Emily Hall, Ph.D. takes videos of marine life along the rim of Amberjack Hole. Various layers in the hole provide habitat for a multitude of species.

Nastassia Patin, Ph.D. swims along an underwater measuring tape that is used for marine life surveys.

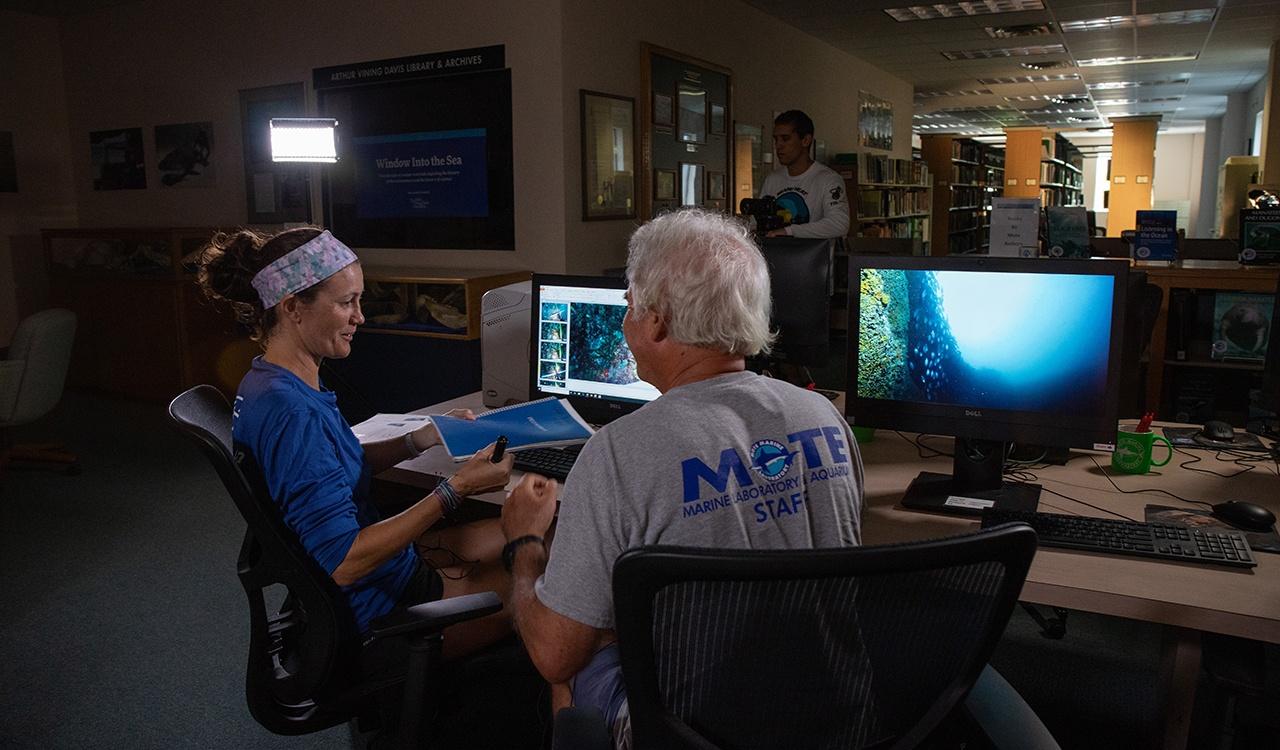

Emily Hall, Ph.D. and Jim Culter review video footage from the underwater surveys.

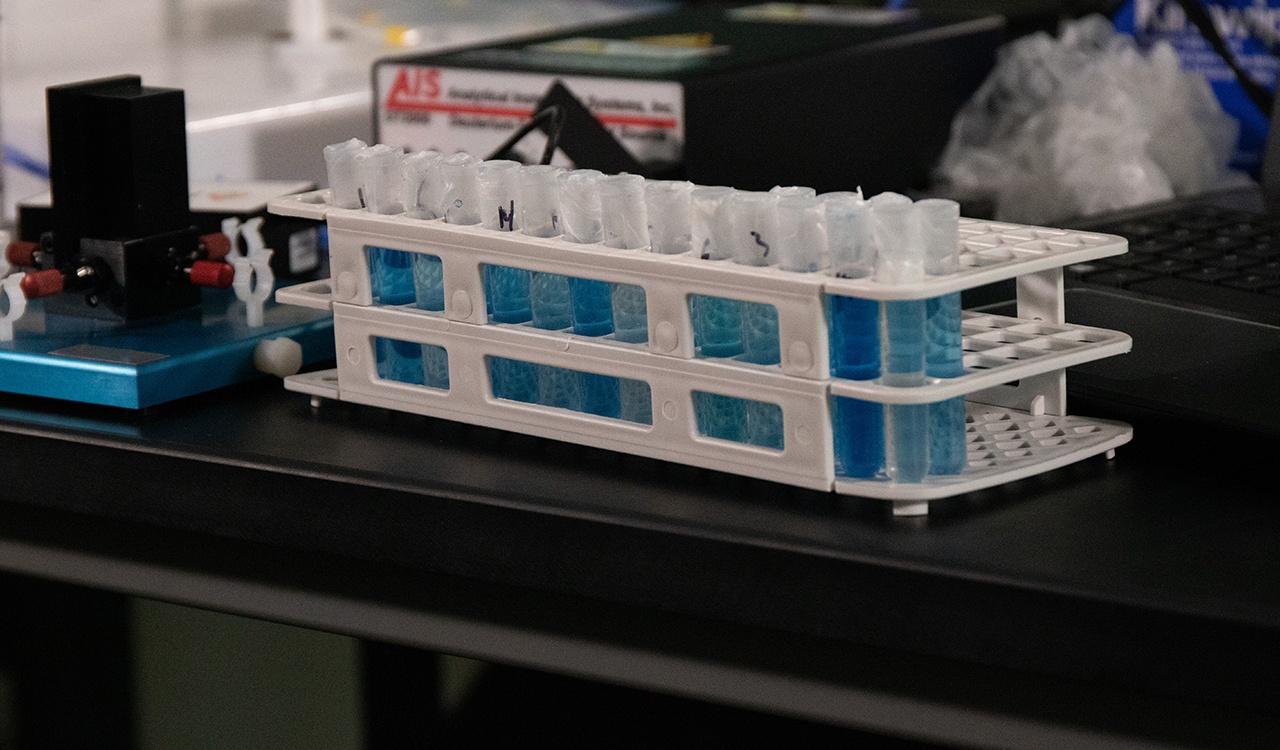

Experts at Mote Marine Laboratory filter water samples collected in and around the blue hole for chemical analysis.

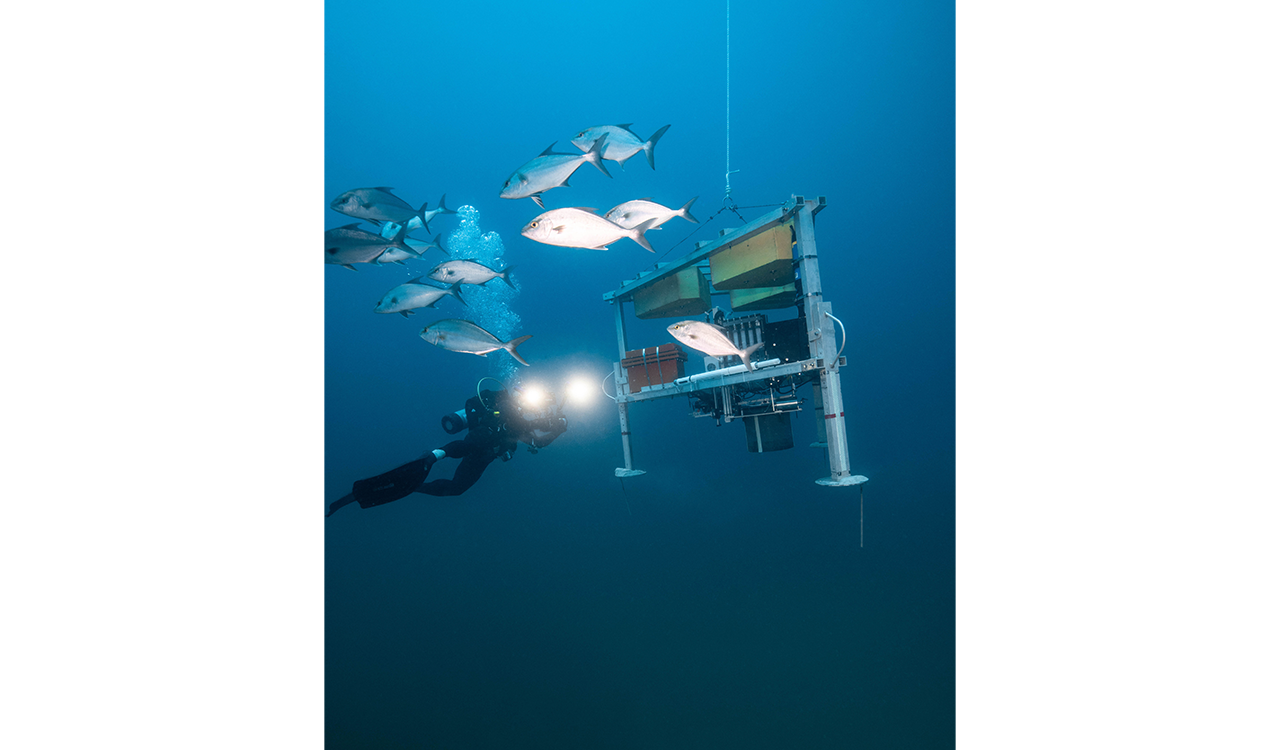

Technical divers join the expedition to help lower and retrieve a specialized lander as well as to collect video footage and samples from the debris pile at the bottom of the hole.

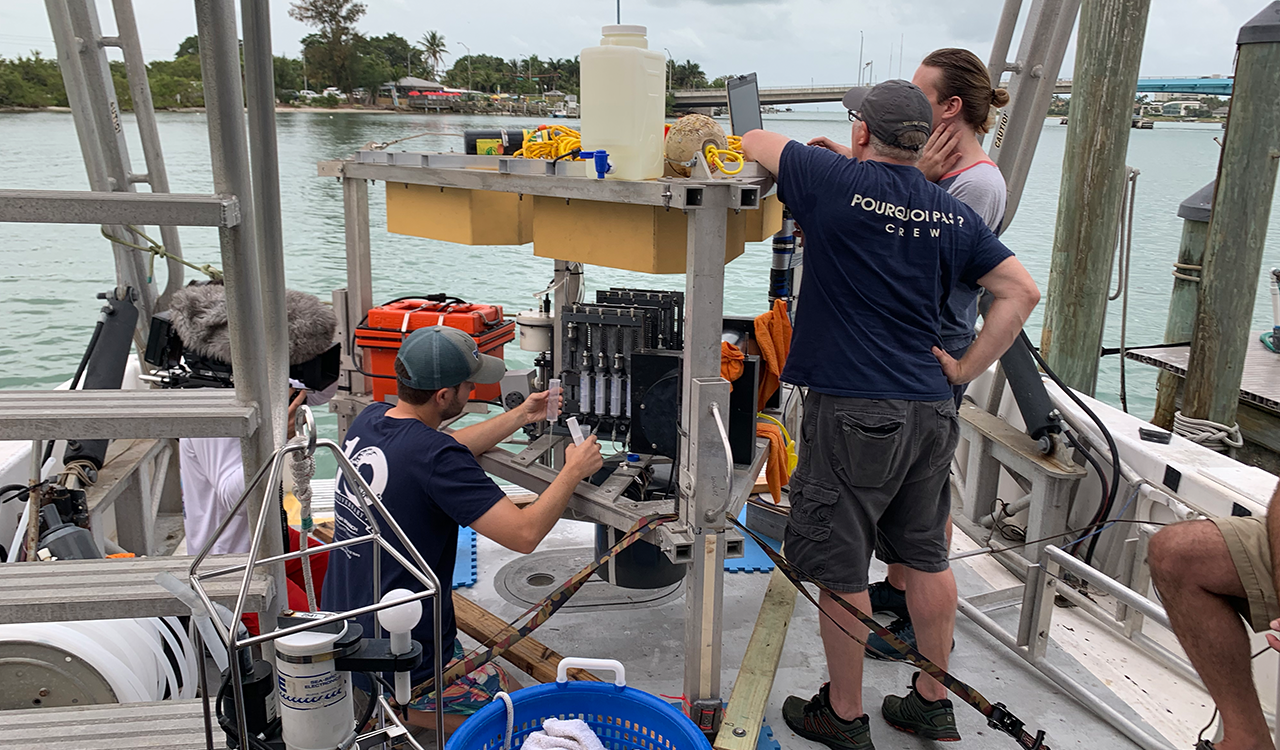

Jordon Beckler, Ph.D. and Martial Taillefert, Ph.D. custom designed a benthic lander with a variety of devices that are able to record data at the bottom of the hole for 24 hours.

A bird's eye view of the benthic lander before being deployed by the ship's A-frame.

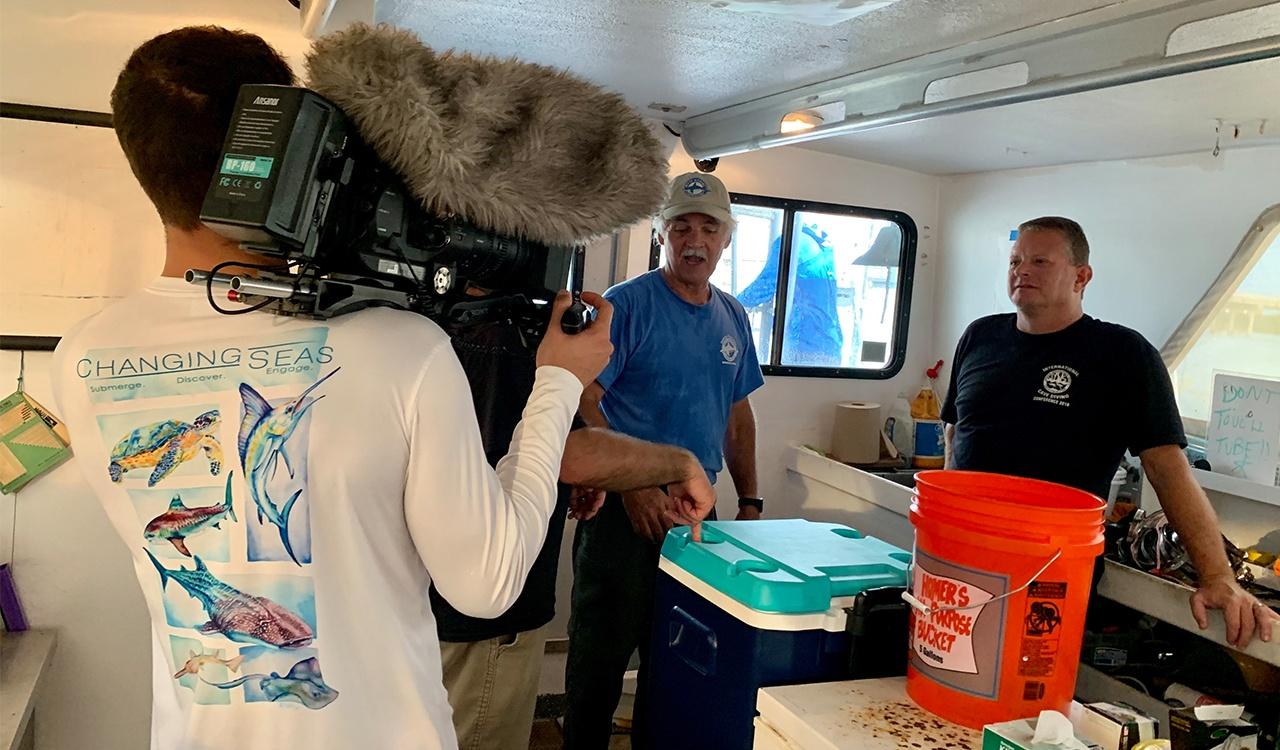

Videographer David Diez films Jim Culter going over plans for the volunteer technical divers that will descend to the bottom of the hole which is at approximately 350 feet.

Director of Photography Sean Hickey films the benthic lander as it ascends from the bottom of the hole, after collecting samples for a 24 hour period.

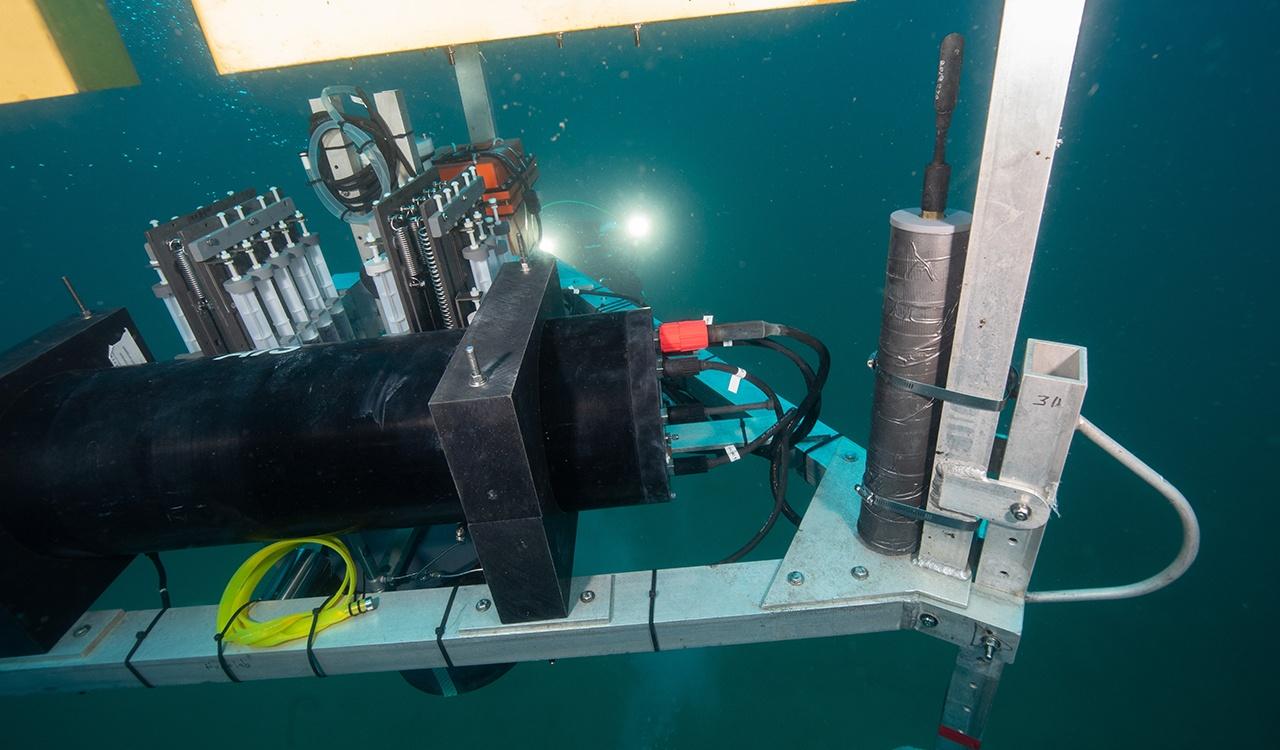

A close-up of the benthic lander underwater.

Director of Photography Sean Hickey on a safety stop in the beautiful, blue Gulf of Mexico waters.

Chemical analyses of samples are conducted back at FAU Harbor Branch, including measuring ammonium and nitrate.

All these analyses create a picture of what kind of life lives in the hole and what nutrients it might provide to the surrounding ocean outside the hole.

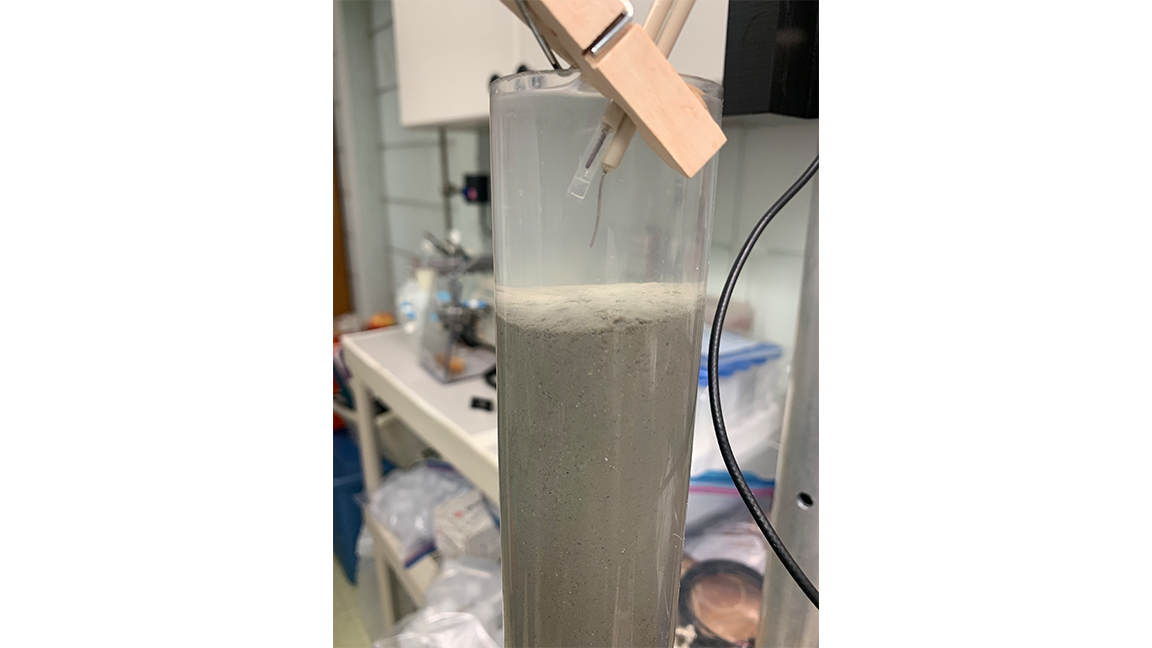

Technical divers descend into murky water right above the rim of the hole - scientists believe this green layer is a sign of high nutrient levels that might be attracting life.

Director of Photography Sean Hickey films technical divers on their long decompression stop. The total dive time can be over three hours long.

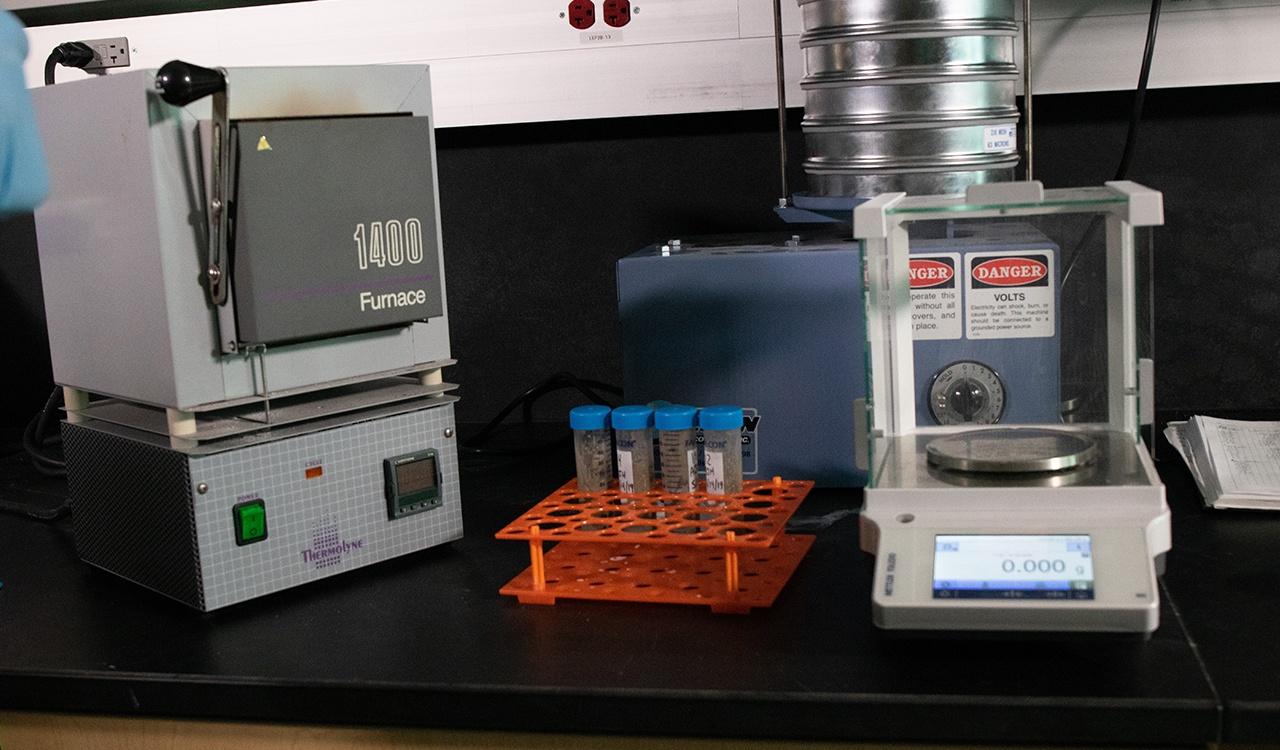

Jordon Beckler, Ph.D. sections sediment collected from the debris pile at the bottom of the hole to learn more about the chemical processes that might be occurring in the mud.

Scientists conduct a variety of analyses of their sediment samples, including measuring the amount of carbon they contain and the grain size of the sediment.

A sample of mud from the debris pile is analyzed in the lab using an electrochemical analyzer.

Producer Kristin Paterakis and Director of Photography Sean Hickey looking forward to a day of diving out on the water!

Some experts believe blue holes formed over 10,000 years ago when sea levels were lower. Blue holes are geologic features similar to springs and sinkholes found in North Florida.

Scientists wonder if the blue holes in the Gulf of Mexico connect to the underground cave system in Florida.