Episode Photos

Scientists with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission's Charlotte Harbor Lab set roughly 120 nets in Charlotte Harbor each month to track the abundance of recreational sport fishes and their prey.

The Charlotte Harbor Lab's Fisheries Independent Monitoring Program has been in place since 1989 and consists of year-round, monthly sampling in Charlotte Harbor.

Fisheries Biologist Matt Bunting from FWC's Charlotte Harbor Lab holds up a snook for the cameras. The fish was caught as part of the lab's monthly sampling efforts in one of the area's tidal creeks.

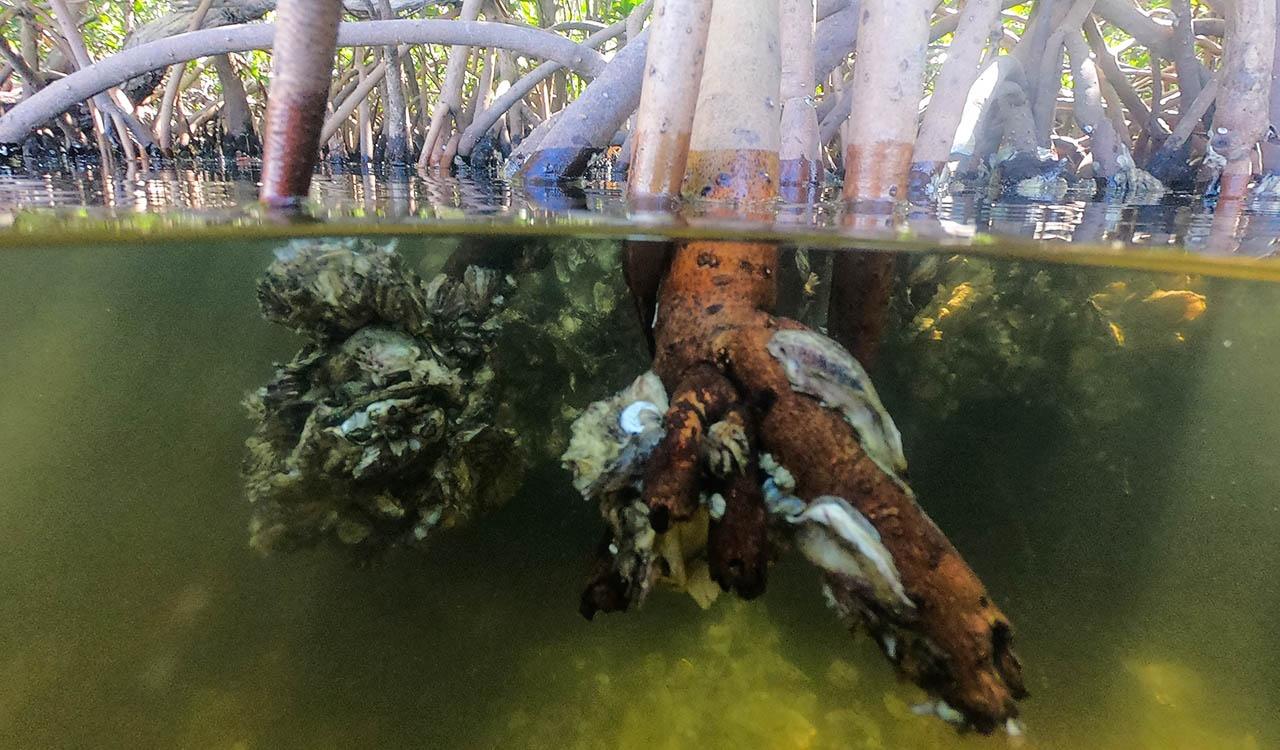

Once common in southern Florida, mangroves have declined by nearly 50 percent over the years due to human development. Mangrove creeks and ponds are important juvenile habitats for snook and tarpon.

A mangrove's extensive root system is a great place for juvenile fish to hide from larger predators that can't access these areas.

The Charlotte Harbor Lab's scientists also set seine nets in remote mangrove ponds which are prime juvenile habitat for snook and tarpon.

All sampling locations are randomly selected. Here a juvenile tarpon was caught in a seine net in a remote mangrove pond.

The scientists identify and measure the fish and invertebrates they catch before returning them to the water.

The Charlotte Harbor Lab's scientists caught tarpon of various sizes in this remote mangrove pond.

Knicknamed the "silver king", tarpon in Florida can grow to reach upwards of 250 lbs and almost seven feet in length.

Charlotte Harbor, Florida, is known among anglers as a great place to catch snook and tarpon.

Tourists come from near and far to fish in Charlotte Harbor's backcountry creeks.

Another group studying tarpon and snook in the backcountry is the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust. Its researchers are focused on restoring impaired habitats, like the Coral Creek area on Southwest Florida's Cape Haze peninsula.

At the Coral Creek site, six abandoned canals with saltwater access were redesigned to make them more beneficial for the fish. The Bonefish & Tarpon Trust scientists conduct monthly sampling of tarpon and snook post-restoration to determine how well the fish respond.

The Bonefish & Tarpon Trust scientists and volunteers catch the fish by pulling seine nets in each canal.

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust scientists and volunteers check the seine net for tarpon and snook.

All the captured snook and tarpon are measured and outfitted with an internal acoustic tag that's similar to the microchips found in pets. Each tag has a unique ID number which the scientists record.

The Bonefish & Tarpon Trust's JoEllen Wilson scans a fish to see if it has been tagged previously. By tagging snook and tarpon over a period of two years, the scientists can determine how many fish are present, if they survive, and how much they grow.

The scientists also use the acoustic tags to track the movements of the fish. Inside the entrance to each canal is an underwater antenna array that can detect the implanted tags and identify fish as they swim by. Some canals have an elevated sill mouth at their entrance, which only provides access during higher tides or storm surge events. This prevents larger predators from entering the nurseries.

Two of the canals in the restoration project lack the sill mouth, allowing water to flow to the nursery areas year-round. The scientists came up with three different canal treatment designs to determine what is most beneficial for the fish.

Tarpon and snook also occur on Florida's east coast, where there are much fewer mangrove forests than on the Gulf coast. One group that's protecting mangrove habitats on the east coast is the Indian River Land Trust, which owns twelve miles of lagoon shoreline.

Starting in the 1950s berms were built around the salt marshes and mangroves on Florida's Indian River Lagoon to help control rampant mosquito populations.

The black salt marsh mosquito needs exposed mud to lay its eggs and reproduce. To prevent this from happening, the impounded mangrove areas are pumped full of water in the summertime when water levels are naturally low.

By the 1980s experts realized that the impoundments were cutting off crucial backcountry nursery habitats from the lagoon, making it impossible for fish to move back and forth unless there was an unusual high water event.

Culverts were installed in the impoundments to allow fish to travel back and forth in the wintertime when water levels are naturally high. In the summertime these culverts are closed and the ponds pumped full of water to prevent mosquitoes from breeding.

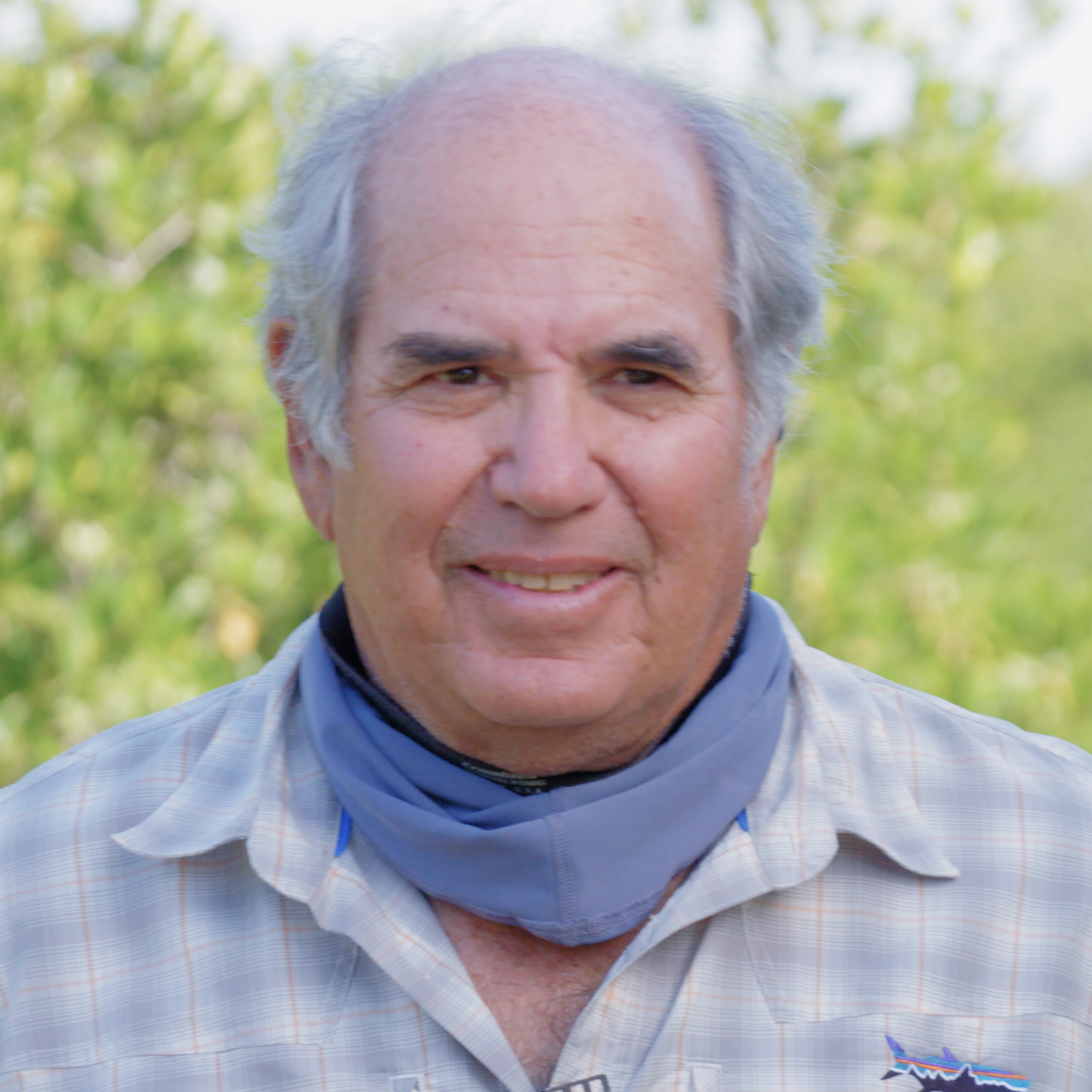

Florida Institute of Technology's Professor Emeritus John Shenker, Ph.D. is part of a tagging project at the Indian River Land Trust's Bee Gum Point Preserve. The research is examining when juvenile tarpon and snook want to leave the impoundments and move to the lagoon.

The sunshine state's unique coastal ecosystems provide fishing opportunities that are unrivaled in the continental United States. But as more and more people move to Florida, many of the natural qualities that attracted them in the first place are in decline.

Mangroves are important habitats for more than just fish - many species of birds and mammals also depend on them for survival.